Note: This essay is an expanded version from my other Substack Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development (FPD) #201. I think that non-therapists would benefit from this particular topic as well.

One of the pioneers of trauma-informed care, Babette Rothschild was asked what she made of the recent increase in trauma awareness: 1

I think by focusing so much on trauma, we’re lessening the importance of all sorts of other stressful things that happen to people. Judith Herman made it very clear in the ’90s, in her book Trauma and Recovery, that if we call everything trauma, then nothing’s trauma.

Still, you hear people these days saying things like, “Oh my God, selling my house was traumatic. I’ve got PTSD from that horrible real estate agent!”

Even in our field, many people I train or supervise feel that trauma should be our primary focus. When I ask them about client issues that aren’t trauma, they counter with, “My clients only have trauma.” I’ll say, “Well, wait a minute, you mean some clients don’t sometimes just have issues with their job, trouble making decisions at the grocery store, or agreeing with their spouse about childcare?”

Therapy-Speak and Concept Creep

These days, it’s hard not to notice a trend that psychological concepts, therapy-speak, and diagnostic labelings are laced in our conversations, like “trauma,” “toxic,” “ADHD,” “autism,” “narcissism.”

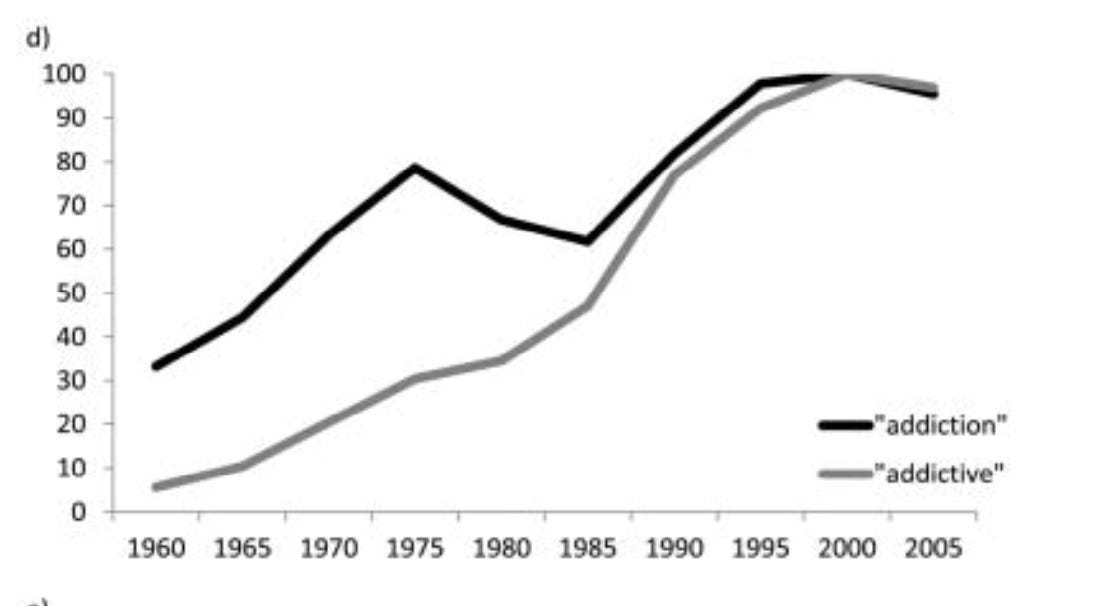

Lets take a look at some specific words and see how they have trended over time:

In his seminal paper Concept Creep: Psychology's Expanding Concepts of Harm and Pathology, Nick Haslam argues that

Concepts that refer to the negative aspects of human experience and behaviour have expanded their meanings so that they now encompass a much broader range of phenomena than before.

There are two types of extension in concept creep:

Vertical: increasing inclusion of milder cases

Horizontal: Increasing inclusion of quantitatively different things, which was previously treated as a different semantic description)

Given that we are talking about mental health related concerns more, one can argue that this has led to destigmatisation, which results in more help seeking behaviour. In turn, we have also become more empathic and sensitive to suffering and maltreatment.

On the other hand, Haslam points out that the phenomenon of concept creep runs the risk of over-pathologising everyday experiences and encouraging a sense of virtuous but impotent victimhood.

RELATED:

I. From psychologist Scott Barry Kaufman. (He also has a very comprehensive podcast called The Psychology podcast. Well-worth listening).

II. Read Nick Haslam’s take on Gabor Maté’s claim on trauma contributing to nearly everything:

What’s in a Name

Names matter.

How we name things have an impact on how we perceive the world and ourselves.

For instance, the term ADHD, which stands for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, seems like a misnomer.

I don’t see it as a lack of attention, because someone with ADHD can actually hyper-focus on a subject of interest. Rather, it’s the lack of ability to corral attention when and where it’s needed.

Moreover, îs an ADHD mind always considered a disorder? It’s only a disorder when one is facing an impairment in a specific context.

Evidence show that there is a positive connection between clinical ADHD and entrepreneurial intentions and action. There is potential self-selection inclination towards those with ADHD starting their own ventures (though does not suggest anything about the performance of their entrepreneurship).2

In another study, compared to non-ADHD peers in a college-student sample, students with ADHD scored higher in originality, novelty, and flexibility.3

A third study suggests that compared to the control group, adults with ADHD reported more real-world creative achievements.4

From a personality-trait perspective, individuals with ADHD are more likely to be high in Openness to Experience, low in Conscientiousness and to a lesser extent Neuroticism.5 The hyperactivity-impulsivity trait is related to low Agreeableness6 and high Extraversion.7

This does not negate the difficulties faced by people with ADHD, like time-blindness, difficulty with disorganisation, working memory challenges, etc. I’ve talked extensively on ADHD in my other Substack if you are interested in exploring some strategies. (Parts I, II, III, IV, V, VI).

Besides trauma and ADHD, have you noticed our obsession with personality quizzes?

As mentioned in Crossing Between Worlds,

The obsession with “personality” had become so crazy in 2019 that Facebook had to ban such quizzes, because more than 87 million people had given away their personal information in exchange for the answer to a quiz. I have noticed people in my clinical practice who pigeon-hole themselves prematurely after taking a personality test, like the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)—often dished out to them in a corporate setting—or an Enneagram test they found online. Notice the language that they would use to describe themselves thereafter: “I am an INTJ” (Introverted, Intuitive, Thinking, Judging) or “I am a Type 3” (The Achiever). To be sure, this can be useful as a springboard for self-awareness. But we must take caution not to over-identify and transfix ourselves with these constructs. You are not an INTJ, an ENFJ, or whatever Type 1, 2, 3…

These are rough clues that give you hints of who you are based on the past projected onto the present. These are not maps for where you are going and who you are to become.

For more about how understanding your personality can help you broaden your nature, see this excerpt from Crossing Between Worlds, What Is Your Nature?

RELATED:

Is there a reason to rename ‘personality disorders’ and call it ‘Interpersonal disorders’ instead?

Recovery without Therapy

Returning to Rothschild, she explains how people recover from trauma, even without so-called trauma therapy:

Rothschild: In the currently popular focus on techniques, the importance of the therapeutic relationship and other sources of support are often forgotten. The literature is consistent: good contact and support in the wake of trauma is what separates people who experience trauma without long-term consequences from those who go on to develop PTSD. And we know that people can and do recover from trauma without trauma therapy.

Interviewer: How do they recover without therapy?

Rothschild: In the same way humans have for thousands of years: they access and utilise all sorts of resources, including a support network. We as clinicians can get so focused on the trauma and processing the trauma memory, that we forget to help people develop the kind of resources that stabilise their daily life. Sometimes helping people improve their quality of life means processing trauma, but sometimes it doesn’t. [emphasis mine]

People recover all the time from trauma without focusing on what it was that happened, be it recent or long past. Sometimes they recover through spirituality, family, good work, nature, friends, even (and sometimes especially) their pets. Many different things can help.

… Sometimes (therapy) can help, though sometimes it can hurt.

Right now, everybody’s looking for a quick fix or new technique that’s going to cure trauma. But even if an intervention works for one person, nothing helps everybody.

Rothschild went on to state that based on three meta-studies that looked at outcomes for several different trauma therapy methods, “no method stood above any other or helped more than 50 percent of people.”

She’s right.

This concurs with the bona-fide trauma treatment and outcome literature. This is also why I recommend clinicians to systematically track outcomes and engagement levels, session-by-session, so that the practitioner can tweak and recalibrate as the therapeutic process unfolds.

What’s “best practice” may not be best for you.

Don’t let the world flood you with overly-medicalised nomenclatures and trending labels peddled in your social feeds.

You are more than a single story; you are a multitude.

p/s: Thanks for reading.

Crossing Between Worlds is now available in all good bookstores.

Daryl Chow Ph.D. is the author of The First Kiss, co-author of Better Results, and The Write to Recovery, Creating Impact, The Field Guide to Better Results, and the latest book, Crossing Between Worlds.

If you are a helping professional, you might like my other Substack, Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development (FPD).

Babette Rothschild’s interview in the magazine Psychotherapy Networker (Nov/Dec 23)

Lerner, D.A., Verheul, I. & Thurik, R. Entrepreneurship and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a large-scale study involving the clinical condition of ADHD. Small Bus Econ 53, 381–392 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0061-1

White, H. A., & Shah, P. (2016). Scope of Semantic Activation and Innovative Thinking in College Students with ADHD. Creativity Research Journal, 28(3), 275–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2016.1195655

Boot, N., Nevicka, B., & Baas, M. (2020). Creativity in ADHD: Goal-Directed Motivation and Domain Specificity. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(13), 1857–1866. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054717727352

Van Dijk, F. E., Mostert, J., Glennon, J., Onnink, M., Dammers, J., Vasquez, A. A., Kan, C., Verkes, R. J., Hoogman, M., Franke, B., & Buitelaar, J. K. (2017). Five factor model personality traits relate to adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder but not to their distinct neurocognitive profiles. Psychiatry Research, 258, 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.08.037

Nigg, J. T., John, O. P., Blaskey, L. G., Huang-Pollock, C. L., Willcutt, E. G., Hinshaw, S. P., & Pennington, B. (2002). Big Five dimensions and ADHD symptoms: Links between personality traits and clinical symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(2), 451–469. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.2.451

The existing evidence between ADHD and Extraversion appears mixed. However, some evidence suggests that Extraversion is a significant predictor of hyperactive-impulsive ADHD symptoms, but not so for inattentive symptoms. See Parker, J. D. A., Majeski, S. A., & Collin, V. T. (2004). ADHD symptoms and personality: Relationships with the five-factor model. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(4), 977–987. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00166-1