Sleeping With The Machine (Part III)

An act of human agency, and not succumbing to The Machine's "inevitability."

In the third and final series on Sleeping with the Machine, we will look at the functional differences between AIs and Humans, and why making a clear distinction between them could be the starting point of this critical point in our history.

Here’s a brief recap from Part I and II:

Is AI's promise becoming our peril?

I examined its benefits, potential impact, ethical concerns like IP theft, and outlining seven Immutable Qualities distinguishing it from humans, such as its lack of embodied experience, meaning-making, and experience of grief.

Building on this, Part II explored the potential Mistaken Identities and how we fall prey to them, especially through sycophancy.

AI's computation, representation, information glut and artificial connection cannot replicate genuine human comprehension, presence, connection, and love.

Once again, her is the Table for an overview:

III. Functions

Here are six areas to consider as we distinguish between AI and Humanity’s functional roles.

1. Algorithmic Recommendations and Idiosyncratic Suggestions

Algorithmic recommendations are ubiquitous in our digital world. Listen to an artist on Spotify, and the platform will show you other artists under “Fans also like.” Look up a book on Amazon and you’d see “Frequently bought together,” “Books you may like,” and “Customers also bought or read.” (not withstanding the sneaky tiny note that some are sponsored ads that makes its way under “Products related to this item”). If you open up YouTube, you are fire-hosted with a ton of video content, related to ones that you have watched before.

Granted, it’s actually a great way to discover new stuff. Related stuff at least. But that’s just one way to discover new things.

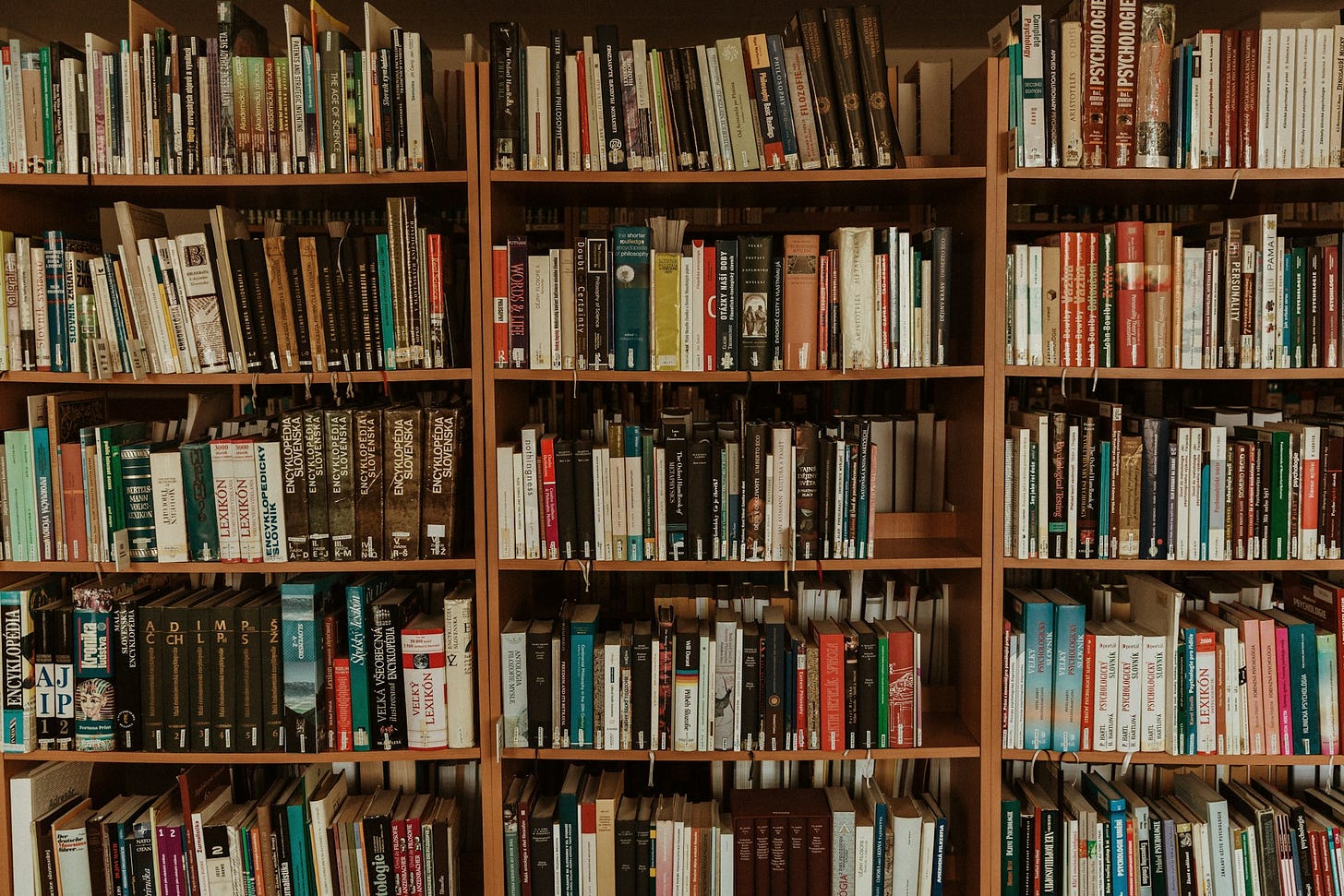

Think of it this way: A google search differs from a library search.1

When you type a query (or a prompt to an AI), you are looking for a specific answer. Your question directs the search in a desirably narrow function.

When you walk into a library, your search experience is different. Even if you have a specific book that you are looking for, you are likely to encounter other non-relevant books that are neighbouring to the physical copy that you are hoping to find. Thus, the search in library creates a widened opportunity for a happy chance encounter.

This is why I love going to bookstores. Like this one.

I love visiting Wellspring bookstore in Singapore. Whenever I visit this specialised bookstore carrying spiritual materials, Peter, the owner, would always have something up his sleeve to recommend me. And I look forward to his recommendations because he is well-read. And, he is likely to suggest a book that resonated with him, and he tells me why.

In other words, I would not have picked that book myself.

Technology triumphs in algorithmic recommendations, because it is a pattern recognition machine. But there is also something to be said about idiosyncratic recommendations. It’s not based only on regressive information, but one that is unique to that of another mind.

(On a related note, if you are looking for a good read, here’s a list of my recommendations of books based on specific topics. See darylchow.com/recommendations).

In Healthcare

Outside of recommended purchases, I would want my family doctor to have the aptitude to combine algorithmic clinical decision making based on the existing evidence, alongside with her own clinical judgement based on her experience. I wouldn’t want the doctor to purely outsource decision making to so-called “evidence-based practice, which is based “on average”—because this does not consider the specific individual’s related profile and co-morbidities—but also based on her own “practice-based evidence.” Needless to say, I also wouldn’t want a physician who ignores the collective evidence and based their entire clinical judgement on intuition alone.

This is to say, in the field of healthcare, I suspect the medical practitioner who knows how to wield technology tools to guide their decision making process, coupled with well-honed clinical skills, are likely to perform better for their patients.

2. Speed of Light vs. Speed of Life

In every attempt to technologically solve problems of our humanity, we go about it by increasing speed.

Yet, at its core, real solutions can only sprout when we slow things down.

This is the real issue at hand. We are resistant to slow things down.

How can we learn to travel at the speed of life, not at the speed of light?

The speed of life is not the speed of light.

Benedictine nun, Sister Joan Chittister says,

When nothing touches me deeply enough to change me, nothing can touch me at all. I learn to say the proper words, perhaps, but I never learn the grace that comes from anger suffered but not spat out, or pain borne and not denied, or love learned and expressed. I go through life on fast speed but numb.

We run the risk of becoming anaesthetised by the barrage of digital information flooding through our nervous system. In turn, with the exception of shocking or outrage materials, nothing else moves you deeply enough to affect you.

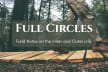

The Hard Way on Purpose

But maybe becoming more efficient in learning makes schools a better place for education? Wouldn’t AI revolutionise education?

The promise of EdTech is to make learning easier. The trouble is, real learning only happens when there is effort involved.

The literature in the learning sciences is clear on this. Making things hard on yourself— or what Elizabeth and Robert Bjork call “Desirable Difficulties” (edited book chapter available here)—enhances learning. Intentionally adding friction to the learning process, which consequently slows you down, is a potent factor that most students aren’t taught to use enough.

Examples include

Pre-testing: initially quizzing yourself before learning a subject instead of just learning for a test at the end,

Retrieval Practice: Pop quizzing yourself instead of re-reading the material, and

Interleaving: changing topics instead of sticking to one topic at a time

The trouble is, learners often prefer ease (e.g., re-reading, cramming), and mistakenly believing that it’s a good way to learn. This is the illusion of fluency.

Moreover, we think that forgetting is an enemy of learning. Turns out, forgetting, and the effort of trying to recall prior knowledge, is actually a great way to increase learning.

Forgetting is not the opposite of remembering; forgetting is a critical process of deep learning.

Benjamin Storm and the Bjorks (not related to the Icelandic singer) says in this study,2

"It appears that rather than undoing learning, forgetting creates conditions that enhance the effectiveness of learning."

In this brilliant Substack post, Learning, Fast and Slow: Why AI will not revolutionise education, Peco and Ruth Gaskovski echoes this sentiment:

Our technologies are often said to “disrupt” society, in the positive sense of innovating. But as Derek Muller (famed YouTube channel Veritasium) points out, while we can be optimistic about how technology might disrupt an area like healthcare, it’s harder to be optimistic about how it might disrupt education.

Should education even be disrupted? What if there is nothing wrong with the fact that we need human teachers, physical books, and classrooms of students who sometimes struggle with learning, but mostly, eventually, figure things out, develop their tortoise legs, and start to run like hares? Maybe we’ve hit the ceiling with how easy education can be, or ought to be?

It’s not that we can’t make any changes to teaching and learning, but what if the real innovation isn’t at the level of technology, but of people?

This gets closer to the heart of the problem. Learning is more than just about getting information and skills into somebody’s head. It happens in the context of relationships.

And relationships cannot be mechanized.

The topic of slowing things down is particularly pertinent to our children. I feel the pull in my bones as an Asian parent. The Tiger parent in me is rattling in the cage. You want your child to succeed. You want them to excel. Heck, wouldn’t it be great if they pick something that they really enjoy and hone in on that and specialise—get a early start?

But the truth is, specialisation is for insects.

Well, now it is for insects and AIs.

Our children need to experience and explore range of activities, rather than hyper-specialise. We can’t just say that you need to learn to code3 because that’s where the world is going, or you need to play the basson because that’s where you’d more likely secure a scholarship. We must follow their sparks, not the splinters of anxiety that we experience about where the trend is going.

In this important podcast interview, Marriane Wolf, neuroscientist and Author of Reader, Come Home, and global education expert Rebecca Winthrop talk about the issues of AI in education, and the issues of offloading cognitive effort to AI for kids.

Even digitised textbook has a profound negative impact on learners. Wolf shared she was asked to testify in Norway about the effects of digitising textbooks and libraries.

- There are concerns that a massive digitisation, like in Sweden, will lead to slipping grades and declining academic performance.

- Norway and Sweden have decided not to digitise for now.

- Korea is beginning to digitise their third-grade textbooks, and they are being cautioned to wait for evidence before proceeding to their peril.

In a study from Singapore, McGill and Harvard indicates that increased digital exposure between ages zero and eight is correlated with reduced attentional capabilities and academic performance. Current data suggests that learning to read is best done with print.

Many of you know this is true intuitively. Reading on a paperback adds more friction in the reading process—and that’s a good thing. Plus, the tactile experience helps.

There’s so much to say about going at the speed of life than at the speed of light (e.g., Read In praise of Slowness by Carl Honoré, or check out any of the Slow Food, Slow Sex, Slow Productivity, or any of the Slow Movement online).

For more on the false promise of EdTech, see this talk:

3. Do Boring Stuff vs. Do Meaningful Stuff

This is where I am slightly more hopeful. AI can help us do and automate the boring stuff, and we do the meaningful stuff.

Or as one ad campaign puts it, “There is work-work. And there is work.”

The promise it that AI can help us to do the boring work-work.

Conversely. there are vast implications on the flip side. We have to be asking ourselves, What is the meaninging stuff? What are the things that I should be pursuing? Where are the trappings?

The pursuit of meaning is not a luxury item. It is a necessity as individuals and as a collective.

In Zen in the Art of Writing, Ray Bradbury says,

What is most important the continual running after loves.

There is happiness in the pursuit. One that is purposeful.

However, even if we are in purposeful pursuit of the things that make us come alive, there is a creeping sense if we do not concertedly assert our agency, even before the coming of AGI and ASI (artificial general intelligence and artificial super intelligence), AI is seemingly attempting to replace creative endeavours like music making, the visual arts, and writing. AI is even set to substitute my profession in psychotherapy.

When AI first came into the scene a few years ago, I made a bet to one of my previous remote assistants that people will use AI for all sorts of things, but not stuff that is related to their emotional life.

How wrong I was.

As I’ve asserted in Part II, we seem to have more and more deep conversations with AIs than with our friends.

According to Center for Humane Technology, Character.AI is being sued after the death of 14-year-old Sewell Setzer (mentioned in Part I), who tragically ended his life after interacting with Character AI’s bots. Character.AI is asking the court to dismiss the case against it, arguing that the outputs from its chatbot are protected speech under the First Amendment. This means that the responsibility for AI-generated outputs lies with the Machine themselves and not the companies that developed them.

Is this the world we want, where companies of AI are not liable?

4. Output Art vs. Joy of Making Art.

This point is related to #3.

AI can be the most productive factory of churning out “art” but never experience the joy of making art.

It’s worth asking what is the role of Art in life. What does Art do for us?

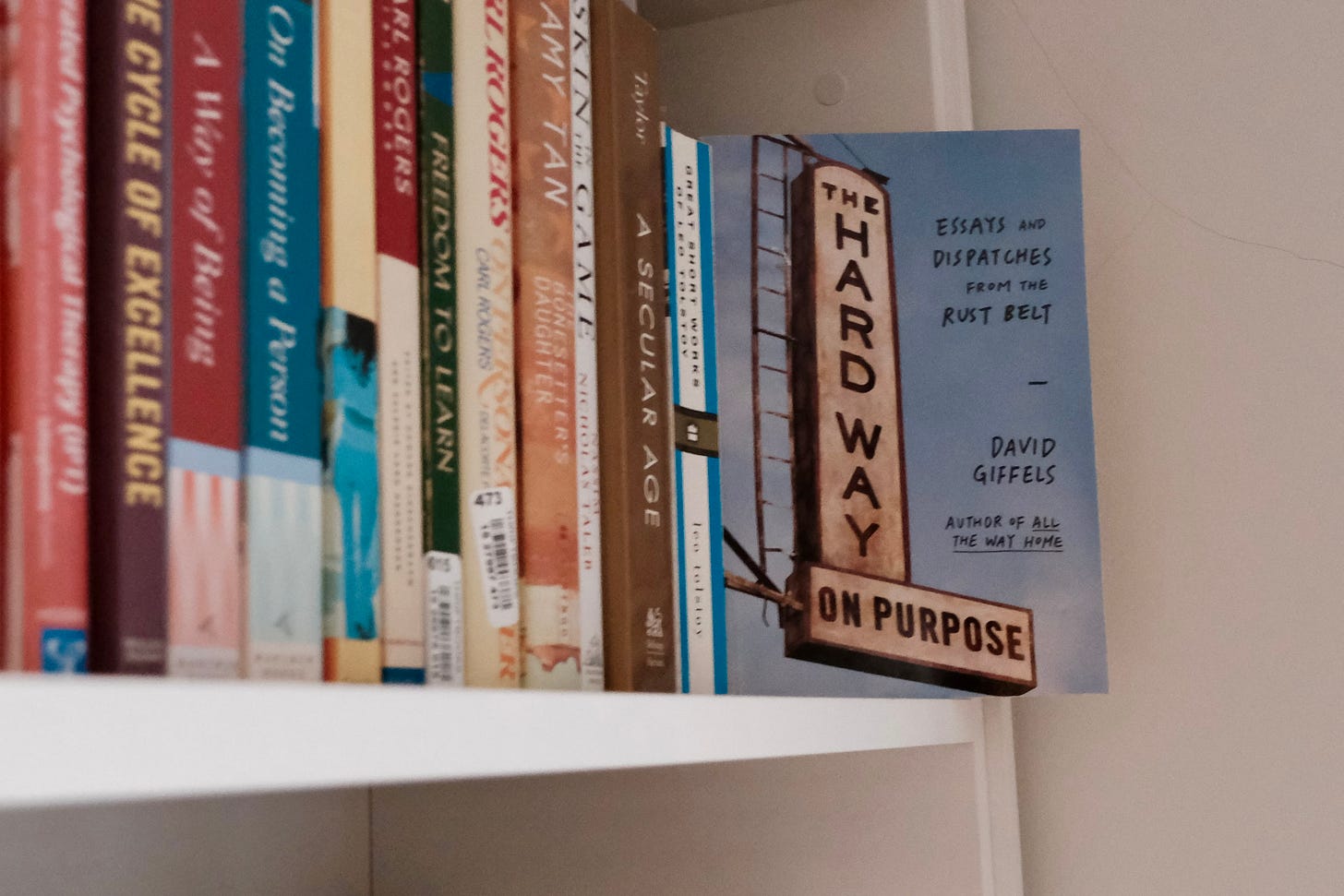

With Dutch artist Bette A., music producer Brian Eno wrote a slim book exploring this vital question: “Why do we need art?”

Here’s a summary of what stood out for me from the book, What Art Does:

Art is a safe way for us to explore feelings.

“They alert you to the range of feelings you are capable of having.”

We make out all the time. It's just that sometimes we don't call it art.

Art is “always a conversation, even if there is only one person involved in the conversation.”

Art is play. “Play is where we start to discover how we feel about things. Feelings are the reward for playing.”

“Play is how children learn. Art is how adults play.”

Art gives us a chance to ask ourselves: “What do I really like?”

“Paying attention to the things we love and that make us feel good and happy isn't an indulgence but a sensible use of our faculties. That's why we evolved them. The problem is that those faculties are constantly overwhelmed by things that other people wished that we liked.”

“The things we care about other things we make art about. We frame them with our attention. Art is proof of care.”

Art brings us together when we can share feelings with each other.

“Art shepherds change.”

Take play. We as a society are more focused on the results of play (e.g., better achievement scores), than the value of play itself. We instrumentalise play. Like most perennial things, such as friendship, wisdom, and play, the benefits are inherent in and of itself.

This means that play—or more specifically, the process of playing—is valuable.

Someone smart once said, “Play is the highest form of research.”

We must reclaim the joy of making art, because this is how we play, this is how we learn, this is how we come to be with each other.

They has been significant voices from artists who are raising the alarm of outsourcing “art” to AIs. I’d talk about two of them here.

1. Hayao Miyazaki

After a presentation of an artificial intelligence model which learned certain movements,4 Hayao Miyazaki, founder of the Japanese Studio Ghibli said,

I am utterly disguised… if you want to make this creepy stuff, you can go ahead. I would never wish to incorporate this technology into my work at all.

I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself.

When asked about the goal of employing AI, one producer said,

Well, we would like to build a machine that can draw pictures like humans do.

Miyazaki: You do?

Producer: Yes.

The video concludes with Miyazaki saying,

I feel like we are heading to the end of times. We humans are losing faith in ourselves.

Great question. Are we losing faith in ourselves?

Watch the video:

2. Nick Cave

The second example is from singer Nick Cave. He has been outspoken about his sentiments of AI in his website The Red Hand Files, where people can submit questions to him.

Here’s one of them:

Q. Considering human imagination the last piece of wilderness, do you think AI will ever be able to write a good song?

— from PETER, LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA

Nick Caves’ response:

It is perfectly conceivable that AI could produce a song as good as Nirvana’s Smells Like Teen Spirit5, for example, and that it ticked all the boxes required to make us feel what a song like that should make us feel – in this case, excited and rebellious, let’s say. It is also feasible that AI could produce a song that makes us feel these same feelings, but more intensely than any human songwriter could do.

… But, I don’t feel that when we listen to Smells Like Teen Spirit it is only the song that we are listening to. It feels to me, that what we are actually listening to is a withdrawn and alienated young man’s journey out of the small American town of Aberdeen – a young man who by any measure was a walking bundle of dysfunction and human limitation – a young man who had the temerity to howl his particular pain into a microphone and in doing so, by way of the heavens, reach into the hearts of a generation.

…What we are actually listening to is human limitation and the audacity to transcend it. Artificial Intelligence, for all its unlimited potential, simply doesn’t have this capacity. How could it? And this is the essence of transcendence. If we have limitless potential then what is there to transcend?”

So to answer your question, Peter, AI would have the capacity to write a good song, but not a great one. It lacks the nerve. [emphasis mine]

4. Making Bots vs. Making Babies

Open AI lied and copied itself to another server when the programmer attempted to delete them. Implications for AI safety is not just some far-fetched horror sci-fi plot anymore.

It seems to me, bots wanna make more bots.

Humans, of course, are the initiators of bot-making. But we are the only ones that can make the really real.

Set in 2027, the movie Children of Men depicts a totalitarian police state, where total human infertility has led to wars and global depression, pushing civilisation to the brink of collapse as humanity faces extinction. In a chaotic world in which humans can no longer procreate, a former activist agrees to help transport a miraculously pregnant woman to a sanctuary at sea, where her child's birth may help scientists save the future of humankind.

I had some initial hesitation on making this point about “Making Bots vs. Making Babies,” but this movie hit a nerve for me. Pushed to such an extreme circumstance in the story, the birth of that single child, is everything worth fighting and dying for.

Even without the dystopic plot, the birth of a baby is a really special and sacred experience. It’s beyond words.

When I held our first-born in my arms, I was shaking with ecstasy. I felt as if I glimpsed a thin slice of heaven. I could see, despite the ordeal of labour, as our baby on skin-to-skin contact with her mother, crawling on her body, reaching for her first breastfeed, my wife was overwhelmed by the same transcendental joy.

The same thing happened for our second child. Again, it’s beyond words.

Since then, never before in my life, have I felt such a deep sense of responsibility. It was not just about being the sole breadwinner, but also about being a good father to my children, and a good husband to my wife.

Despite the weight of it all, it is a good thing. I can ask for no other thing but the responsibility of the people I love. There is a sense of freedom to take up this responsibility.

My children are not mine; they are my guests.

Henri Nouwen said,

… children are not properties to own and rule over, but gifts to cherish and care for. Our children are our most important guests, who enter into our home, ask for careful attention, stay for a while, and then leave to follow their own way. Children are strangers whom we have to get to know.

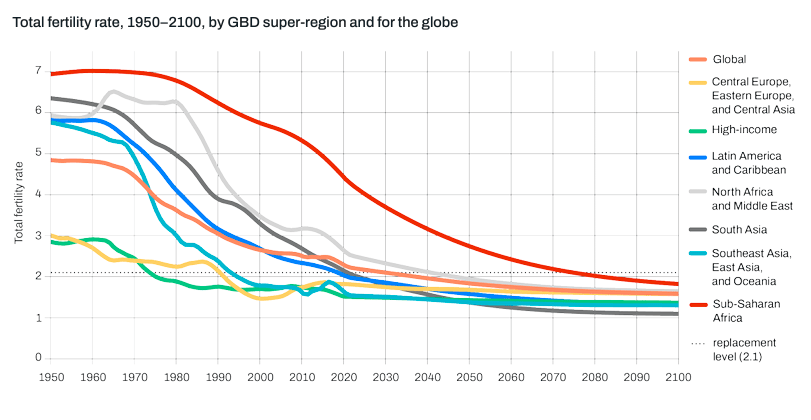

However, we are having fewer and fewer “important guests” in our lives. Global birthrates are on the decline.

This is relevant to the discourse between AIs and Humans because it’s so easy to lose sight of the meaning of it all. I’m not saying that everyone should have children or that replicating our genes is the be-all and end-all.

I mentioned Neil Postman’s questions in Part I that we should all be asking ourselves: What problem does the technology claim to solve?

Technology is not solving our most human challenges—not just about declining birthrates, but also how we care for families, support the wellbeing of young people, and protect those living at the margins of society.

In the lat Rabbi Jonathan Sack’s book, The Home We Build Together, he argued that the only cultures that survive are those who are capable of “making sacrifices for the future.”

The future also requires our restraint.

As ethicist Tristan Harris points out in his recent TED talk, for humanity’s sake, the age of AI is asking for us to exercise restraint (see Parting Thoughts below).

5. Useful vs. Valuable

Folks in a local butcher shop learned that Michael Longley is a poet.

They couldn't help themselve and had to ask the Irishman why he does such a useless thing like writing poetry.

“What use is poetry?”

Longley replied, "It is without use…useless. But it is valuable.”6

The world is not just in need for useful things, but more than ever before, the world needs valuable things.

Things that are true, good, and beautiful.

Parting Thoughts

We are at an inflection point.

We can make the pre-mortem analysis7 here, as well as learn from our history.

If we don’t learn from history, the price goes up.

We see this taking place with the use of social media. Thanks to a large part of people like Jonathan Haidt, Jean M. Twenge et al. and their tireless body of research, we are slowly waking up to harm done on especially the young.

For instance, Australia has taken the unprecedented step to ban social media for under 16’s. Interestingly, many youths that I meet are in agreement with this ban.

It is worth repeating, we can ground ourselves with questions like the ones Neil Postman proposed:

What problem does the technology claim to solve?

Whose problem is it?

What new problems will be created by solving an old one?.

The most important thing is to protect the most important thing.

As I’ve mentioned at the outset of this series, I have limited expertise in AI. That said, I hope my attempts to cover as in-depth as I can on this topic, through the list of items on the table above, may help you raise critical questions in your work and personal life, and your relationship with the Machine.

How technology evolves is not inevitable. We are agentic beings. Rebecca Winthrop views this period as an Age of Agency. Not the Age of AI. We must exercise our agency.

Agency is crucial here, especially since those behind the Machine don’t even fully understand how AI is doing what it’s are doing. Sure, you don’t to know how a car works in order to drive a car. But what if even your mechanic and car manufacturer has no clue of how it works when things break down?

Doesn’t that sound scary to you?

To conclude, I have two parting points:

1. Collective Immune System

Let me turn this over to others who have better expertise that I do and have thought more deeply about this than I have.

You might know Tristan Harris from the documentary Social Dilemma. He was previously a Google Design Ethicist, and is the co-founder of Center for Humane Technology.

He makes the argument of how we can avoid dystopia and a world of anarchy and chaos by taking what he calls “The Narrow Path.” (you can also read this on CHT’s Substack.

In his most recent TED talk, Harris concluded,

Your role in this is not to solve the whole problem. But your role in this is to be part of the collective immune system.

…There is no definition of wisdom, in any tradition, that does not involve restraint. Restraint is the central feature of what it means to be wise.

2. Body, Soul, and Play

In Part II, I highlighted the differences between Representations vs. Presence. Recall that Iain McGilchrist argues that we have increasingly tilted towards the left hemisphere’s way of thinking. While the left hemisphere is more analytical and controlling, it is prone to paranoia and narcissism and deluding itself. This overshadows the right hemisphere’s way of processing the world, which is a more wholistic and integrative view.

How can we tilt back towards our humanity, especially at this important turning point?

There are three broad ways of returning to the true master of the hemispheres—the right—which is through our embodied selfs, our souls, and through play.8

Body:

No matter what some transhumanists want to make of this, we are ultimately a biological and embodied creature.

Here are some suggestions to engage our minds and bodies, which aren’t two separate things:

Move

Dance

Sing

Make analog art

Make real love

Cold baths

Hold the hands of someone you love…

Soul:

While the Spirit transcends, the Soul brings us back to the ground. This is why soulful activities could even be any of the activities in Body.

Subject to your belief systems, here are some suggestions:

With your complete and undivided attention, listen to music.

Write a letter to someone you love. (Longhand, on paper).

Have a conversation about some unspokens in your life with someone you trust (see We Are Hungry for Depth).

Pray

Meditate

Contemplate

Lie on the grass and look up to the clouds.

Read a good book (and letting it read you).

Get on the floor and play with your child (or any child!).

Experience Beauty, and let it touch and move you. Slowly.

Play

Finally, play it away!

Do something fun for fun sake. No outcome, no goal, no expectations.

Recall Brain Eno’s words: Play is how children learn. Art is how adults play.

Some clues of what constitute as play: Look at what you liked doing as a child.

Look also at some of the activities above. Here are some more suggestions:

Throw a frisbee with your friend

Board or card games

Tinker with some DIY stuff

Escape Rooms

Go bowling

Mini-Golf

Play with your children, and play what they want to play.

…Pick any hobby, just for the heck of it!

Remember: we have an inner and outer-life. Take care to nourish them.

P/S: Please pardon typos. This took me an entire day to write, and have not had the chance to proof edit thoroughly.

PP/S: Let me know what your thoughts about this series on AI and us below. Thanks.

Recommended Substacks on the AI Topic:

Here are some recommendations if you would like to learn more about AI from a critical lens:

The Abbey of Misrule (look at his back catalogue regarding The Machine. Can’t wait for Paul Kingsnorth upcoming book, Against The Machine.)

The Honest Broker (though not quite AI specific, Ted Gioia is one of the most erudite writer I know of).

Crossing Between Worlds is now available in all good bookstores.

Daryl Chow Ph.D. is the author of The First Kiss, co-author of Better Results, and The Write to Recovery, Creating Impact, The Field Guide to Better Results, and the latest book, Crossing Between Worlds.

If you are a helping professional, you might like my other Substack, Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development (FPD).

I believe I first heard this phrase from organisation psychologist, Adam Grant.

Storm, B. C., Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2008). Accelerated relearning after retrieval-induced forgetting: The benefit of being forgotten. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 34(1), 230–236. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.34.1.230

It’s up for debate if AI is going to make learning to code obsolete. I doubt it will.

As far as I understand, not quite the AI that we have at present.

I remember when I first heard Smells Like Teen Spirit as a teen when it was first released. I was shocked, awed and floored. It made no sense at first. “What the heck was that?” On repeated listen, it starts to moves you like a possessed creature—like the headbangers on their MTV.

Listen to the interview with Michael Longley: https://onbeing.org/programs/the-vitality-of-ordinary-things/

A pre-mortem, coined by cognitive psychologist Gary Klein, is an exercise to anticipate and imagine as clearly as possible, when things fail. Then we can reverse engineer it.

In his book, The Master and the Emissary ,McGilchrist calls them “Body, Spirit and Art” (pp. 438-445).

Thanks Daryl. I enjoyed reading all 3 parts. It has opened my eyes in a helpful way. AI has to serve us or we will end up serving it.