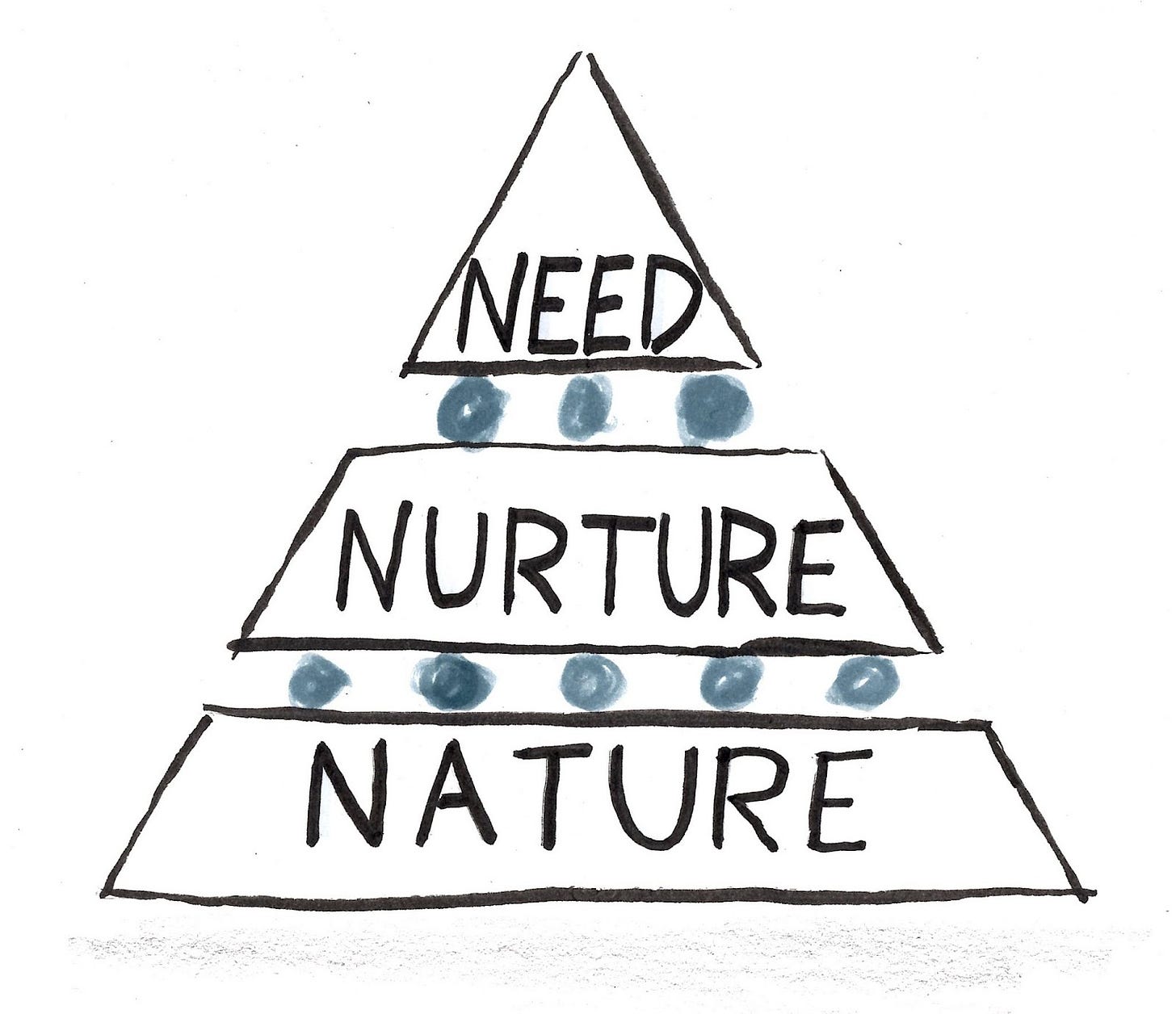

Nature, Nurture, Need.

For those navigating significant life transitions... Mother your nature, informed by your needs.

Thanks for reading Full Circles: Meditations on the Inner and Outer Life. If you are new here, learn about me, and the About Page.

These posts are meant to be what Lewis Hyde describes as a “Gift.” What this “Gift” concept means for me is that

Nothing is expected out of you.

I hope you receive it.

I hope this animates you.

I hope you spread the love to others.

Below is an excerpt of the upcoming book, Crossing Between Worlds: Moving and Being Moved Through the Transitions of Life.

I’ve previously talked about how we get lost while trying to find our way in making significant changes in our lives.

Before we get to the heart of the book, which contains 15 Paradoxes (see below for a snapshot), I will talk about the relationship between Nature, Nature, Need, and why understanding this framework in a deep way can help you move—and be moved— toward a life that is waiting for you.

You Might Not Need This Book

Though it is not a good marketing strategy for me to say this, I thought I should make it clear: you can do without this book.

People have been navigating and adapting to changes in their lives long before the printing press was invented. They seemed to do just fine with all the resources they had. In fact, many people go through transitions in life without any kind of guidance.

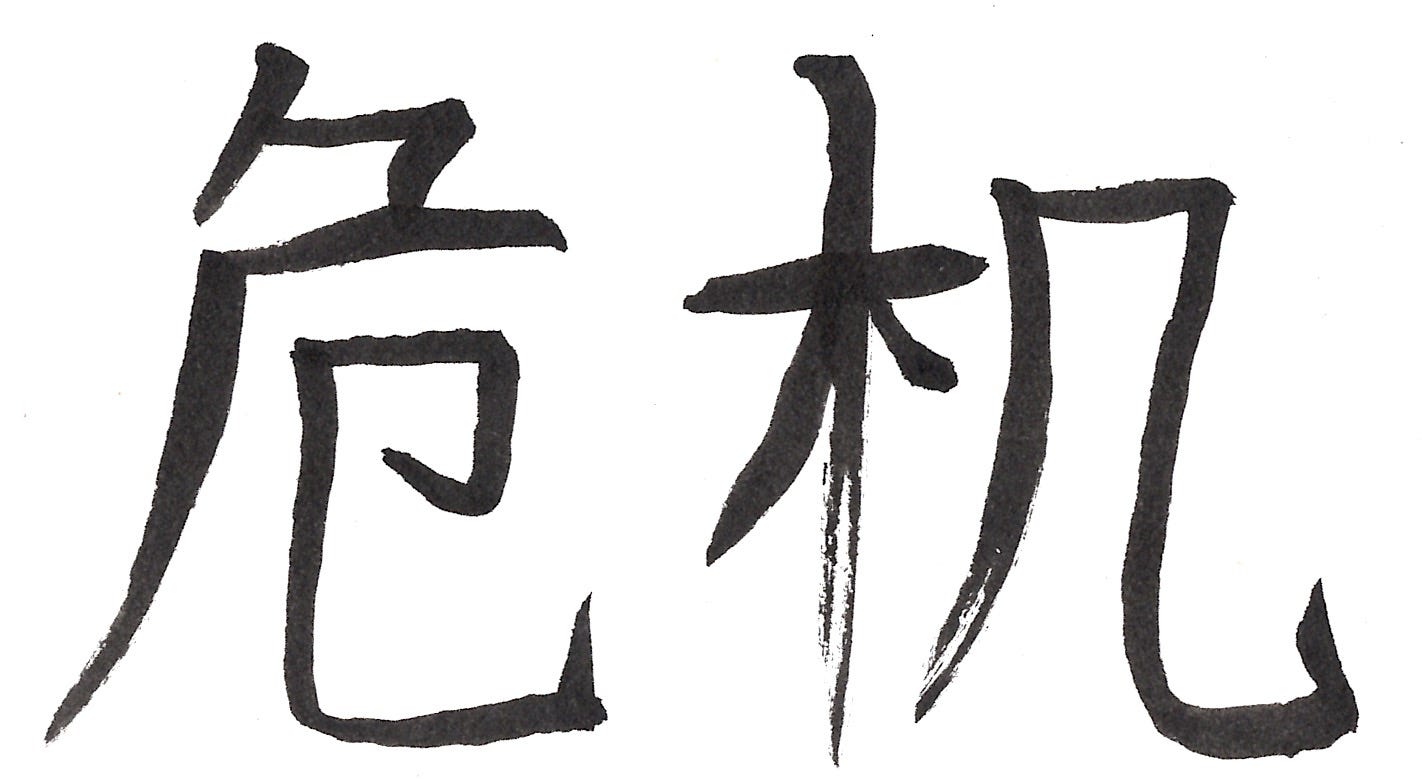

In Chinese, the word “crisis” (Wéi Jī) means a time of both danger and opportunity. The one reason this book exists is to help you see and seize the opportunity in a time of shake-ups, to take heed of your deep desires and fan the amber within you, so that you get a fighting chance to experience deep joy in this one life.

You will notice that Crossing Between Worlds serves as a vast map of possibilities (more on that in the 15 Paradoxes).

This book is not about having more information or catchphrases; it acts as a catalyst for change. It is designed to help you experience life. It is not just about having more ideas; it’s about becoming who you really are. In other words, this book will ask of you more than you would ask of yourself on your own.

Don’t waste a crisis.

Bridge-Crossing

Over the past 20 years in my clinical practice as a psychologist, this is where I meet and walk alongside fellow travellers: on a bridge.

The journey of Crossing Between Worlds is a defining period in one’s life. Give or take, you’ll probably experience only a handful of such transitions in your lifetime. These periods are often coloured with darkness, uncertainty, ambiguity, fear, suffering, and grief. It’s unfortunate that we have a proclivity to reduce our experience to diagnostic labels and reach for the nearest medical or psychological explanation, thereby leading us to water down this liminal state as a “mental health” issue.

In our attempts to make sense of it all, we use various clinical terms, from depression and anxiety to ADHD, trauma, and others. But when you become too quick to name things,1 you fail to follow the calling path in front of you, the new world that is beckoning you to inhabit it. While the embodied experience and symptoms of such a period can be discomforting and distressful, they are signals, and not the issue in and of themselves. Sometimes, all it takes to shift our state is to ask ourselves, What’s making me depressed? What has happened that led me to feel this way? Not everything has a clear cause and effect, but it would do us good to have a better understanding of our nature, how we nurture ourselves through the emotional needs that we have (more on that later, in “Nurture Our Nature”). By viewing our emotional pains solely from a medical perspective, we run the risk of treating only the symptom and not the problem.

Moving from an old story to a new one is akin to crossing a bridge. This bridge is often wobbly. Your footing is unsteady, your mind is racing, and your heart is riddled with anxiety as you take each step.

And yet, at the brink of it all, the opportunity arises for us to see things differently. As you move along—and you might not fully grasp this while you are doing it—the seasons are changing. Your needs are no longer the same as they once were; what’s required of you previously no longer applies in this upcoming fresh territory.

But the movement between worlds is not exactly new. Like the seasons, we move in circles. Periods of crises might vary, but the inner-challenges that surface have similar patterns and schemas. Most of us will face at least three to five major life disruptions, or as author Bruce Feiler calls them, “Lifequakes.” Hence, it makes perfect sense to learn deeply from past reckonings when you are at the fork in the road.

This book is about listening to the needs and seasons that arise in times of change and crisis. It is about moving and being moved. “Moving” implies acting upon our intentions and tilting the sails to help us move in accordance. “Being moved,” on the other hand, is to allow ourselves to be touched and inspired by what unfolds in front of us, even when—or rather, especially when—it is not our choice.

“To move” is to resist becoming the victims of our circumstances. “To move” is an act of will and responsibility. “To be moved” is to allow ourselves to be touched by what’s in front of us, and to utilise that as a mobilising force (See Paradox 15. “Control and Surrender” in the book).

Researchers in human emotions offer a fascinating insight. A review article by Janis Zickfeld and colleagues suggested that being ‘moved’ should be treated as a “distinct emotion.”2 Sensations of being moved include tears, chills, a lump in the throat, goosebumps, and warmth in the chest. When seen in this light, it’s easy to understand why the experience of being moved is often considered a passive one, i.e., not something we can actively control. Let me do my Chinese teacher proud and point out that in Mandarin, “being moved,” Gǎn Dòng [感动], literally translates as “to feel movement.”3

Here’s another interesting point to note. The lexeme being moved not only implies approach and prosocial tendencies, but it also suggests "insight, meaning, and personal growth."

This book does not offer a fixed path. Nor should you simply take someone else’s path. Artist Austin Kleon says, “Some advice can be a vice.”4

You must ultimately forge your own path. There is no formula, only a form, a structure that can guide you. Treat this book as a structural scaffold. You pull it down once you are done.

Main Idea

This is the central idea of the book:

Our nature is designed to be nurtured,

informed by our needs and the season we are in.

We are going to unpack, one at a time, each of the four factors (nature, nurture, need, and season) embedded in this single sentence, and then develop a personalised map for the way forward using the Personalised Paradoxical Profile (P3), which will help you as you are Crossing Between Worlds.

Nature → Nurture → Needs → Naming the Season → Complete the P3 → Read the 15 Paradoxes → Revisit Your P3 → Course of Action

Nurture Your Nature

“The major problems in the world are the result of the difference between how nature works and the way people think." — Gregory Bateson.

What Is Your Nature?

One of the most beneficial things you can do for yourself is to figure out your nature. The Latin natura, or Nature, means both birth and character. Let’s unpack each of the two.

By Birth

By Birth, we are predisposed to a certain temperament, and somewhat bound by our genetic underpinnings. Differences in temperament from an early age becomes apparent when you observe your children. One might be easy going and leap non-hesitantly into the playground with other kids, and the other might be very sensitive to the external environment and needs time to observe others on the playground before they set foot in the sand.

The different shades of temperaments shape our personality. Personality is a set of enduring patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours that make an individual unique. Our personality colours how we see the world. Not only does it cause us to perceive things differently from others, but our unique personalities also lead us to consider different facts. For instance, when dealing with conflict at work, a highly empathetic individual is more likely to consider the feelings and perspectives of others involved, while a logical person is more likely to prioritise effectiveness and efficiency towards the end result. Likewise, individuals higher in Openness to Experience—one of the Big Five personality constructs that we will talk about later—are less likely to conform to pre-existing beliefs and are more willing to consider information that contradicts their existing views.

Why is understanding personality constructs so important? In an in-depth course on personality, Jordan Peterson argues it’s because you are a person who is situated in a social world, and you have a personality and must contend with other personalities.5 Different personalities have different proclivities in their moral and political ideologies. One would imagine that our moral and political beliefs are primarily based on reasoned judgements, but in his book The Righteous Mind, Jonathan Haidt notes that our moral foundation and political ideology are shaped by our temperaments, more so than we imagine.

For example, individuals high in Conscientiousness, characterised by traits such as self-discipline and adherence to rules, may place a strong emphasis on moral values related to loyalty and authority, which are key aspects of conservative moral foundations. On the other hand, individuals who are high in Agreeableness, characterised by traits such as compassion and cooperation, may prioritise moral values related to care and fairness, which are central to liberal moral foundations.

Given the above, and based on the current empirical understanding, what is a useful framework that can help us understand our nature a little better? What are the “givens” in our temperaments from birth? I would argue that the Five Factor Model (FFM), commonly referred to as the Big Five Personality Traits, is one of the most practical tools for understanding ourselves.

An easy way to remember these five factors is to use the acronym OCEAN. It stands for Openness to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. See the following table for an elaboration of each trait, along with its corresponding advantages and disadvantages when pushed to the edges.

Table 1. The Big Five Personality Construct

You might be interested in understanding more about yourself through the lens of the Big Five Personality Construct. I suggest three options for doing so in Appendix B of the book.

Whichever version you decide to explore with, treat the Big Five as a “vocabulary” you can use to recognise your nature, as well as a way to see others as they are. However, do not treat your temperament as fixed. You can broaden your nature based on where you are going—especially as you are Crossing between Worlds. You’ll discover and unravel more about yourself than you would expect. (In each of 15 Paradoxes, I provide specific suggestions for certain personality factors, under Broaden Your Nature).

By Character

If one facet of our nature is By Birth, the other is By Character, which comes from the Greek word, kharakter, or chisel. In a sense, when we move towards our intentions and face the inherent challenges along the way, our character is formed and “chiselled” into being.

Our temperament is not destiny. Dan Gilbert says,

Human beings are works in progress that mistakenly think they’re finished.

Tempting as it seems, and as useful as they can be, we should not completely outsource the process of understanding ourselves to a personality test. This might seem contradictory to what was mentioned earlier regarding the Big Five Personality construct, but the key is to have a clear and balanced view about how we can understand who we are.

In Annie Murphy Paul’s book The Cult of Personality Testing, she points out that these personality tests contribute to oversimplified categorisations of complex human beings, potentially leading to discrimination, biases, and misguided decision-making. For instance, there is still a prolific use of personality tests by one in five Fortune 1,000 companies to assess candidates for executive roles, expending an estimated $2 billion on such assessments.6 Yet the evidence is poor on the use of personality tests to predict job performance.7

The obsession with “personality” had become so crazy in 2019 that Facebook had to ban such quizzes, because more than 87 million people had given away their personal information in exchange for the answer to a quiz.8 I have noticed people in my clinical practice who pigeon-hole themselves prematurely after taking a personality test, like the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)—often dished out to them in a corporate setting—or an Enneagram test they found online. Notice the language that they would use to describe themselves thereafter: “I am an INTJ” (Introverted, Intuitive, Thinking, Judging) or “I am a Type 3” (The Achiever). To be sure, this can be useful as a springboard for self-awareness. But we must take caution not to over-identify and transfix ourselves with these constructs.9 You are not an INTJ, an ENFJ, or whatever Type 1, 2, 3… These are rough clues that give you hints of who you are based on the past projected onto the present. These are not maps for where you are going and who you are to become. As Derek Sivers notes,

Putting a label on a person is like putting a label on the water in a river. It’s ignoring the flow of time… “I’m an introvert, so that’s why I can’t.” No. Definitions are not reasons [emphasis mine]. Definitions are just your old responses to past situations. What you call your personality is just a past tendency. New situations need a new response… Nature changes seasons at regular intervals. So should you.10

We are, however, about to create the map for the territory ahead of you.

Nurture Our Nature

We needn’t get caught up in the debate about “nature vs. nurture.” Our nature is designed to be nurtured. Each of us has a unique predisposition and proclivity. Our task in this lifetime is to cultivate what’s inside of us. This is our responsibility. As the great jazz musician Miles Davis put it, “Man, sometimes it takes a long time to sound like yourself.”

Why would it take a long time to figure out a way to fully express who we really are? Perhaps because there is so much noise to cut through and so many competing voices inside of us to wrestle with.

There’s also a big difference between what’s right and what’s right for you. It’s easier than you think to get caught up in the former—and take for granted the latter. Why is this so? Because of the allure of the competing voices outside of ourselves, from those who try to peddle us snakeoil, telling us stories about what we should want, what we should need. It’s much easier to follow the pack than it is to heed the small voice that speaks from our nature.

Nurture your nature. You can tilt the direction and push towards the edges of your development. You can identify aspects of your personality and stretch towards where you want to go. The goal is not to fixate on what you've been given. Rather, it is what you do with what you have that matters. Ultimately, the journey in Crossing Between Worlds is to broaden your personality.

Our job is to mother our nature. Like a gardener, we plant the seeds, and we give them water, we give them light—perhaps not too much for some types—and make sure they are rooted in good soil, nourished by good fertiliser. After all, good things grow from shit.

~~~

Here’s where we are so far:

Nature → Nurture → Needs → Naming the Season → Complete the P3 → Read the 15 Paradoxes → Revisit Your P3 → Course of Action

Why Needs?

Most of us know more about “shoulds” and less about “needs.”

As I write this at a cafe, I’m looking at two toddlers with their grandparents. Sitting in their high-chairs, I don’t think they can make the distinction between shoulds, wants, or needs. Their moment-by-moment wants and needs are met by their caregiver. Maybe they are hungry; maybe they are thirsty. Maybe the younger brother just did a number two in his diaper. Or maybe as the grandma says to them now, “Nap-nap time.”

Physical needs are obvious. Emotional needs are less so.

Emotional needs remind us of a distant truth that we deny. We don’t like to feel needy. We feel too “dependent,” overly reliant, and disempowered from being a fully autonomous creature. But that is how we come into this world: needy, crying and utterly dependent on our caregivers.

Needs are like beacon lights, flashing signals to tell you, “Hey, look here!”

Emotional needs are universally non-negotiable. This is a strong statement. This means that everyone has needs hidden in plain sight, and no one is exempt from them.

What are these non-negotiable emotional needs?

Most of us are familiar with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, with self-actualisation at the top of the pyramid. Personally, I don’t find that pyramid useful. Turns out, Abraham Maslow never put the “hierarchy of needs” on a triangle. Some management consultancy firm in the 1960s did that.

Early in my career as a youth worker, I was exposed to the teachings of the late William Glasser. He was quite a non-conformist, vocal about his belief that his profession of psychiatry was over-medicating people. One of Glasser’s theories provides a useful framework for me. Glasser defined five Basic Needs:

i. Survival

ii. Love and Belonging

iii. Autonomy

iv. Freedom

v. Fun

You’ll notice that only one of these needs is physical. The other four belong to the emotional domain of our inner lives.

As I will elaborate later, our needs change at different times and may even be contradictory, especially when we approach critical junctures that impose significant changes around us. But just take a moment and contemplate these questions:

What are some of your unmet needs right now?

Where is the pain?

What’s missing at this point in your life?

Allow yourself the spaciousness of contemplation during times of transitions.

In my clinical practice, after we’ve explored what has led the client to make an appointment with me, asking variations of the above questions seems to evoke a visceral response for many people. Most clients unconsciously let out a sigh as they reflect on them, as if someone is gently pressing on an aching point on their body.

When I asked Josephine, who was in her mid-50s dealing with a bout of anxiety, “What’s missing in your life? What do you need?,” she couldn’t come up with a response.

“I have no idea,” she replied.

Given that she wished to be able to get out of her house and go to the shops without fear and anxiety crippling her, I initially thought she might talk about the need to be more in control or to have more personal agency. After I walked her through the menu of five basic needs, she jumped in. “You know what? I’m really lacking fun in my life.”

This took me by surprise. Since her children had moved out and she’d had a health scare a few years ago, she’d found herself more and more redrawn into her shell and disconnected from her long-time friends.

Isn’t it interesting that “Fun” is on that list? Quite often, we neglect a sense of playfulness. We think we need to double down on earnestness when we are going through troubled times. Yet play is a potent antidote to depression. Improv teacher Keith Johnstone says,

Many teachers think of children as immature adults. It might lead to better and more ‘respectful’ teaching if we thought of adults as atrophied children.11

When we neglect or ignore our emotional needs, psychological symptoms present themselves. Like a fire alarm going off when something’s burning, these symptoms are signals. If you treat only the symptoms, it is like flicking off the annoying siren without actually putting out the fire.

In short, needs are your guiding light. They point to a direction, and consequently, a set of actions is asked of you.

Our task is to nurture our nature, informed by our needs.

In the next article, I will talk more about how this relates with figuring out the season that we are in. Thanks for reading.

Crossing Between Worlds is now available in all good bookstores.

P/S: Complete a short quiz to get a comprehensive How-To guide, to help you make significant life transitions and changes.

Thanks for reading Full Circles: Meditations on the Inner and Outer Life. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Daryl Chow Ph.D. is the author of The First Kiss, co-author of Better Results, and The Write to Recovery, Creating Impact, The Field Guide to Better Results, and the latest book, Crossing Between Worlds.

If you are a helping professional, you might like my other Substack, Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development (FPD).

To be clear, at times, having a label to define the problem that we have can bring a huge sense of relief. For instance, to be formally diagnosed as autistic in adulthood can bring great comfort to some, since this helps the individual not only to make sense of their challenges as a child, but also helps them navigate the world ahead of them, i.e., learning social skills systemically or learning that it’s ok to retreat when they has been in a noisy environment for longer than they can manage due to sensory overload.

Janis H. Zickfeld, Thomas W. Schubert, Beate Seibt, & Alan P. Fiske. (2019). Moving Through the Literature: What Is the Emotion Often Denoted Being Moved?: Emotion Review, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177_1754073918820126

I failed at Chinese at my GCE O Levels exams, twice. I couldn't read 80% of the text, so I did my Chinese oral exams in English, much to the amazement of my classmates.

From Steal Like An Artist, by Austin Kleon.

If you are interested in taking an in-depth understanding on Personality, I highly recommend Jordan Peterson’s course Discovering Personality courses.jordanbpeterson.com/personality. I’ve learned more from this than any other personality course or books that I’ve read combined. The Big Five Personality questionnaire comes free with this course.

Morgeson, F. P., Campion, M. A., Dipboye, R. L., Hollenbeck, J. R., Murphy, K., & Schmitt, N. (2007). Reconsidering the Use of Personality Tests in Personnel Selection Contexts, Personnel Psychology, 60(3), 683–729. [https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00089.x](https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00089.x)

Taken from Benjamin Hardy’s book Personality Isn’t Permanent.

See also You are a Multitude. fullcircles.substack.com/p/multitude

How to Live, p. 87 by Derek Sivers.

From Impro: Improvisation and the Theatre, by Keith Johnstone.

Can we connect ?

I write ✍️ on Nature, Humanity, Travel and connect my soulful thoughts into writings

Let's support and work together