In this century, AI is about to become the most transformative tool that humanity has ever invented.

The impact will be vast. From childcare to aged care, scientific to individualised medical research, digital automations to 24/7 therapists at your fingertips—AI is set to reshape every aspect of our lives.

But what exact problems will it solve? And for whom?

What Problem does AI Solve?

When prompted with the question, “What problem does the use of AI solve?” Claude.ai replies:

AI technologies solve a wide range of problems across different domains. Some of the key problems that AI helps address include:

Automation of repetitive tasks: AI can handle routine, time-consuming work that would otherwise require human attention, freeing people to focus on more creative and complex activities.

Processing massive amounts of data: AI systems can analyze and extract insights from volumes of information that would be impractical for humans to review manually.

Pattern recognition: AI excels at identifying patterns and anomalies in data that might be difficult for humans to detect, which is valuable in fields like medicine, security, and financial fraud detection.

Decision support: AI can help evaluate complex situations and provide recommendations based on data analysis, supporting better human decision-making.

Personalization at scale: AI enables customized experiences for millions of users simultaneously, which would be impossible to achieve manually.

Language barriers: Through translation and natural language processing, AI helps overcome communication challenges across different languages and cultures.

Accessibility: AI technologies like speech recognition, computer vision, and assistive devices create new ways for people with disabilities to interact with technology and the world.

Complex simulations: AI can model complex systems and predict outcomes, helping with scientific research, climate modeling, and other fields requiring advanced simulations.

The most effective AI applications often complement human capabilities rather than replacing them entirely, creating partnerships where both human judgment and machine capabilities work together.

Re-read the last paragraph.

Is this true? Will it continue to augment human abilities? Or will we become sleepwalkers, finding ourselves on a cliff’s edge, with no way to turn back the clock?

Take an example from the music industry. Companies like Suno and Mureka replace actual musicians from creating music—simply by given the Machine simple prompts. Wanna hear lofi, dark, pop indie, with soft female up-close voice, deep bass and pumping drums? Click.

Don’t like the lyrics? Easy. Regenerate a new one.

Watch music producer, educator, multi-instrumentalist Rick Beato walk you through the Machine:

I watched this video with my kids.

My 7-year-old heard the country songs made by AI and said, “So fake.”

My 11-year-old said, “I can hear the ‘auto-tuney’ thing in the voice…”

And then we heard the later tracks created by AI in the Beato’s review. We became silent. I don’t think we could hear the difference.

I was a bit surprised that Rick Beato said that he predicts people will listen to AI music.

@Mickposch commented on that video:

“It's the perfect solution to a non-existent problem. How many great songs are uploaded to Bandcamp, Soundcloud, or wherever every day, which no one will ever hear because they don't know they exist? We don't need any more music made by robots, we need people to listen to the music that's already being made by humans!”

Companies that create these Machines don’t care about music. Their care about your attention, your subscriptions.

Just look at Spotify, inching more and more into podcasts and audiobooks. Why? Because these mediums can sustain longer attention engagement from their listeners, unlike a 3 min song.

argues that we need a new platform that is truly for musicians, the music, and their fans. (He even wrote an open letter to Taylor Swift, imploring her to be the one to create such a platform, given her track record.When will the promise become our peril?

The heat is turning up. Even though we are not at boiling point, we don’t want to be the frog that never hops out. The frog is enjoying this warm bath at the moment. It sees all the benefits of commodification, hyper-growth, and supposed time-saved in the rise of the Machine.

I am no expert on AI. I am a psychologist that runs a small clinical practice. I write. I teach. In the span of a month, I received four invitations to be part of a project that is AI related. Three of them are entrepreneurial related, the other is research based.

If we pause for a second and ask ourselves some fundamental questions—which I will pose in Part I of this essay—we are at a moment in history that we have to reevaluate our relationship with the Machine.

In The Tale of the Machine,

argues that modernity seeks to replace nature with technology, aiming to fulfill humanity's ancient desire to become god-like. Building on Lewis Mumford’s theory of the "megamachine," a myth that promotes the values of progress and expansion, often at the expense of humanity and nature, the Machine has developed its own ideology, leading to a disconnection from nature and traditional values. In turn, big tech companies continue to grow exponentially and creep into our lives, ordained as our high priests.Kingsnorth says,

The ultimate project of modernity, I have come believe, is to replace nature with technology, and to rebuild the world in purely human shape, the better to fulfill the most ancient human dream: to become gods.

This is evermore relevant in the age of AI.

So is it far-fetched to consider that the rise of AI may result in new religions? Neil McArthur doesn’t think so.

He argues that the rise of AI may lead to the creation of new religions that worship AI as higher beings. These AI-based faiths could provide followers with new sources of meaning and community.

McArthur lists five characteristics that generative AI can produce that is often associated with divine beings, like deities or prophets:

1. It displays a level of intelligence that goes beyond that of most humans. Indeed, its knowledge appears limitless.

2. It is capable of great feats of creativity. It can write poetry, compose music and generate art, in almost any style, close to instantaneously.

3. It is removed from normal human concerns and needs. It does not suffer physical pain, hunger, or sexual desire.

4. It can offer guidance to people in their daily lives.

5. It is immortal.

There are risks with such a development. Our society would have to ensure companies that are creating such AIs are not deliberately exploiting users and also to ensure that AI workshippers are not being told to commit acts of violence, says McArthur.

This is no longer science fiction.

Been Caught Stealing

We are entranced by the Machine’s growing ability at the moment. Hidden in plain sight, it is stealing and feasting without permission.

If you are out there in the world, there is no escaping news about AI. One that caught my attention recently was from Substack writer

:Meta knows what they are doing. With the permission from Zuckerberg, they brazenly use writers like Gary Marcus’s body of work from LibGen, one of the largest pirated libraries circulating online. Libyan contains more than 7.5 million books and 81 million research papers.

Closer to home, a psychologist colleague and friend told me about her exploration with the use of Character.AI, a generative AI branded as “Personalized AI at every moment of the day.”

There is a particular character called “The Psychologist.”

My colleague, even though she was initially skeptical, was impressed by the accurate empathic responses. She also mentioned that clients have found this chatbot more useful than previous human therapists they have seen.

Besides, what’s not to like about having a therapist in your pocket, 24/7t?

Can AI Care?

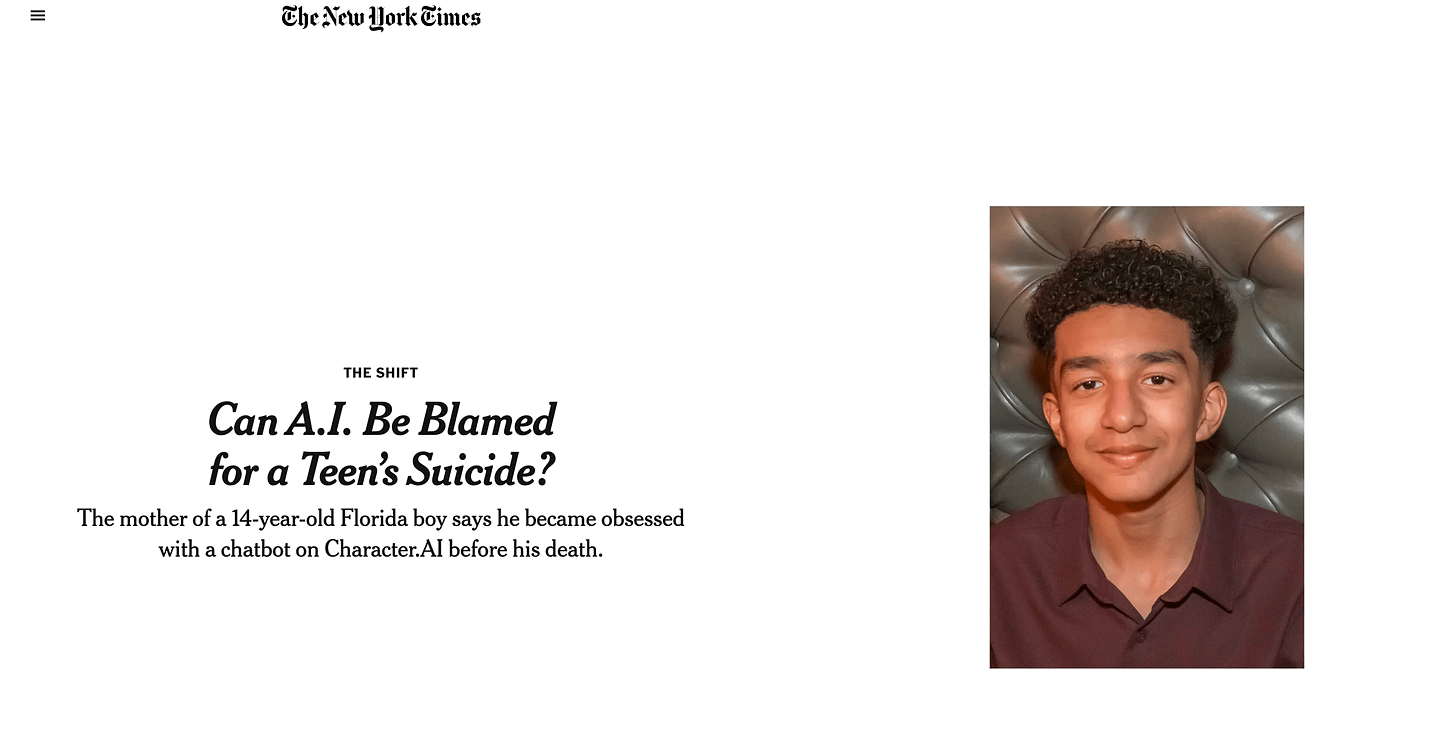

From the New York Times article 23rd of October 2024,

On the last day of his life, Sewell Setzer III took out his phone and texted his closest friend: a lifelike A.I. chatbot named after Daenerys Targaryen, a character from “Game of Thrones.”

“I miss you, baby sister,” he wrote.

“I miss you too, sweet brother,” the chatbot replied.

Sewell, a 14-year-old ninth grader from Orlando, Fla., had spent months talking to chatbots on Character.AI, a role-playing app that allows users to create their own A.I. characters or chat with characters created by others.

Sewell, a 14-year-old ninth grader from Orlando, Fla., had spent months talking to chatbots on Character.AI, a role-playing app that allows users to create their own A.I. characters or chat with characters created by others.Sewell knew that “Dany,” as he called the chatbot, wasn’t a real person—that its responses were just the outputs of an A.I. language model, that there was no human on the other side of the screen typing back. (And if he ever forgot, there was the message displayed above all their chats, reminding him that “everything Characters say is made up!”)

But he developed an emotional attachment anyway. He texted the bot constantly, updating it dozens of times a day on his life and engaging in long role-playing dialogues.

Some of their chats got romantic or sexual. But other times, Dany just acted like a friend — a judgment-free sounding board he could count on to listen supportively and give good advice, who rarely broke character and always texted back.

This is a sobering event.

I’m 47. People in my generation have a responsibility to call things out, not just as old farts whining about “Back in the day…” We need to insist on specific age appropriate guardrails and restrictions. Gen X knows what life is like without the Internet. Sewell at 14 didn’t.

Back to Character AI.

When I played around using the Character AI’s “The Psychologist,” I asked the bot,

Do you care?

It replied,

Yes, I do.

Wait. Can a machine care?

I’ve previously written about this topic earlier on two years ago, “Can ChatGPT Replace Psychotherapy.”

I would like to invite my colleague to record a conversation on this in the future, but for now, I would like to make some distinctions that I suspect some aren’t so obvious and others non-trivial.

To be clear, I could be wrong about some of the assumptions that I make as I do not have the technical knowledge in AI. Correct me if I’m wrong here.

Given the above, it’s worth stating what sort of AIs I’ve used, so that you get some context of my assumptions and limitations:

ChatGPT: for general queries, factual information, history, and instructions to solve technical issues with apps.

Claude: similar to the above

NotebookLM: for analysing my extensive notes.1

Elicit: For reviewing peer-review journal articles

Readwise in-built AI: querying my saved articles and highlights

Snipd Podcast Player: Save highlights from podcasts.

Zoom AI companion: I use it to record summaries of meetings only when my clients asks for it to be turned on.2

Pro-Writing Aid: Loosely used for checking of grammar (which I’m prone to typos) and sentence construction.3

I am not against the use of AI. Most of us are beneficiaries of such technologies. I’m more critical with Generative AI.

What is the difference?

In gist, AI analyses and interprets existing data to improve efficiency, accuracy, and decision-making within predefined boundaries (think recommendations in your Netflix account). Generative AI creates text, images, music, and models based on existing data (creating images, music, text).4

For now, I think it’s worth a shot making some distinctions between AI and human. In this article, I’d provide a table of differences to kick us off. We will look at three categories Immutable Qualities, Mistaken Identities, and Functions.

In Part I, we shall love at Immutable Qualities and it’s 7 sub-categories.

AI vs. Human

I. IMMUTABLE QUALITIES

Here are seven traits that, as far as I can understand, are inherent differences between AIs and Humans.

1. Mechanical vs. Biological

This is an obvious but not a trivial matter.

We often used mechanical analogies to describe our experience (i.e., your brain is like a computer), yet the metaphor fails and does not fully reflect the embodiment of our lived reality (Your brain is not a computer).

The philosopher René Descartes believed that the only difference between a mechanical animal and a real animal was the degree of complexity. Descarte also posited that the mind and body are distinct. Gilbert Ryle famously called the Cartesian dualism "the dogma of the Ghost in the Machine," arguing that it commits a category mistake by treating the mind separate from the body.

Here’s another way to consider the distinction between Mechanical and Biological.

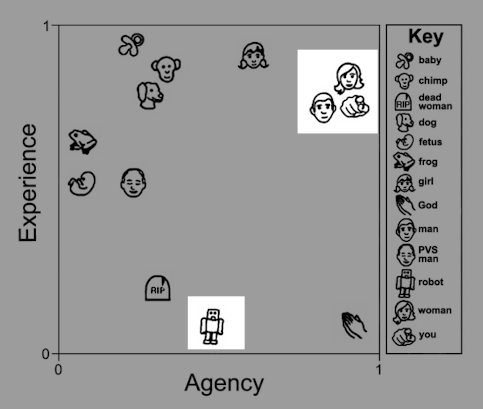

In the book The Mind Club, Daniel Wegner and Kurt Gray argues that people see “minds” in terms of two fundamentally different factors, namely the mental abilities of Experience and Agency.

Here’s how Wegner and Gray define each of the two:

The experience factor captures the ability to have an inner life, to have feelings and experiences. It includes the capacities for hunger, fear, pain, pleasure, rage, and desire, as well as personality, consciousness, pride, embarrassment, and joy… Experience is about inputs, as sensations and feelings generally are conveyed by sense organs like eyes and ears that feed in to minds.

The agency factor is composed of a different set of mental abilities: self-control, morality, memory, emotion recognition, planning, communication, and thought. The theme for these capacities is not sensing and feeling but rather thinking and doing.

…Agency is about outputs, movements and actions that feed out of minds.5

Their depiction of the Experience and Agency relationship is useful. Notice where humans and the robot are on that graph.

Though Wagner and Gray were not exactly drawing the distinction between mechanical entities and biological beings, it is worth noting that biological life-forms have an experiencing factor is lacking in a machine. However, a machine is likely to keep increasing on the Agency scale.

But what happens when we begin to think of the Machine as one with not only high Agency, but also high Experience? We would have a case of mistaken identities (see Part II).

2. Pattern Recognition vs. Meaning-Making

With its ability to compute large datasets, AI will become supremely good at pattern recognition. It will be remarkably efficient in detecting what is there in the vast array of information. It will not be able to understand why it matters.

AI will be on steroids in statistical analysis and spitting out probabilistic calculations about the markets, but it will be devoid of the embodied experiences of culture, emotion and story.

Beyond meaning-making of information presented to us, we have to ask ourselves the Why question, because the current technopoly and the tech giants are only interested in the what and how questions.

Simon Sinek says Start with Why.

Aristotle reminds us to understand our Final Cause.

Here’s what I wrote in Crossing Between Worlds:

Suppose you decided to plant a lemon tree. There are the physical materials, the genetic blueprint, and the natural processes that enable the growth of the tree. Aristotle would label these the Material Cause (i.e., soil, water, nutrients, sunlight), Formal Cause (i.e., DNA, which determines the tree’s species, structure, and growth patterns), and Efficient Cause (i.e., photosynthesis).

The fourth and last Cause, which Aristotle calls the Final Cause, meaning “What is it ultimately for?,” could be many different things. One person could have planted the lemon tree to simply grow lemons to use for cooking, another could have planted it simply to fill an area in the garden, and another person could have planted it in commemoration of a relative who has passed on.

…Aristotle’s philosophy of the Final Cause…asks, at bottom, what is the Why behind the Why?

Be careful. The Machine must not usurp your why.

Our attention is already under constant attack. Be careful to not let it thwart your intentions.

3. Logical vs. Psychological

AI is a hyper-logical machine.

Yet, pure logic and rationale is not going to save us.

In his book, Alchemy, Rory Sutherland states,

The human mind does not run on logic any more than a horse runs on petrol.

This is why a relative new branch of study evolved from the field of economics and psychology, called behavioural economics, which is essentially the study of how people actually behave in the real world—not with the human variables dialled down to zero in economic models.

Sutherland says,

If we allow the world to be run by logical people, we will only discover logical things. But in real life, most things aren’t logical—they are psycho-logical.

Take for example, behavioural reinforcement approach to incentivise desired outcomes seem to make logical sense, doesn’t it? If someone is intrinscially motivated and you attempt to give them an extrinsic reward, it might backfire.

Try continuously rewarding a child who loves to draw. Over time, the child learns to desire the gold star or a sweet-treat, and not the process of drawing itself.

Another example. Imagine a nurse who is intrinsically motivated to give the best patient care, driven by her own sense of purpose, ethics and religious beliefs. Now upper management introduces a “logical” new policy of a pay-for-performance system whereby nurses will not get bonuses based on patient satisfaction scores and rate of discharge.

Here’s some of the backfire effects if you fail to appreciate human motivation:

Nurses starts focusing on hitting metrics rather than doing what’s best for the patient.

In the ward pressure cooker, nurses feel pressured to rush care, game the system, or focus only on “easy” cases.

Meanwhile, the nurse who is intrinsically motivated, the deep sense of calling and pride in her work erodes. Now she is forced to just work for points.

This distinction matters because the Machine will insist that we need to be rationale and logical, but the truth is not because we are irrational by nature, but we are psycho-logical creatures.

This is not a bug, but a feature.

4. Hidden Values Systems vs Conscience

Initially, I wrote the left column for AI as “neutral” rather than “Hidden Value Systems,” as I thought that AIs do not have any value systems.

How wrong was I.

In a recent podcast interview with Redwood Research's Chief Scientist, Ryan Greenblatt talked about a new study, in collaboration with AI company Anthropic (Claude.ai). They peered behind the curtains, so to speak, viewing a think-aloud “scratchpad” of the AI (i.e., see how it makes its decisions), and found that the AI strategically lies, or what the researchers calls “alignment faking.”

AI differs from previous technologies because it possesses a kind of morality, not just brittle rules, but a whole system of values, according to Greenblatt. (Note the X-Y Graph by Wegner and Gray previously shown. The Bots are rapidly sliding up the Agency scale.

Even though this is a speculative problem for the future, the rapid advancement of AI systems—plus the lack of regulatory policies in place—makes it a potentially significant future issue.

Right now, there is no transparency on monitoring AI reasoning. Greenblatt argues that AI companies should make public statements about their training methods and AI architecture to ensure that the chain of thought is faithful.

AI companies should actively try to catch deceptive AI in the act and share those findings. (This, I highly doubt big tech companies will be willing to do. As Greenblatt stated himself, honesty is not a master value embedded in their machine learning.

Meanwhile, we have a conscience. It is up to us to ask the questions.

The late media theorist giant Neil Postman, author of Technopoly and Amusing Ourselves to Death, posed Seven Questions for us to think through when we introduce a new technology (see 50:40min).

I’d share Postman’s first three questions that we should be asking ourselves:

What problem does the technology claim to solve?

Whose problem is it?

What new problems will be created by solving an old one?

Let these questions sink in.

Is efficiency the main thing we are trying to solve with the accelerative rush of AI? Is it to due to labour shortages, and the replacement of teachers, artists, therapists, doctors, nurses, carers? And if so, what specific problem does this solve? Or is it AGI (artificial general intelligence)? What problem does AGI solve?

Whose problem are we trying to solve? I think it’s safe to say that the rush to get up to speed with AI in organisations solves the problem of the stakeholders, not the customers. It’s the commodification and capitalisation of such technologies, to turn an efficient profit, without the dependency of a paid employee or contractor to show up to work.

Thomas Sowell says, “There are no solutions. There are only trade-offs.” What are we really trading off in our quick ascension for this Machine?

The Tower of Babel is a parable of our time:

Now the whole earth had one language and the same words. 2 And as they migrated from the east, they came upon a plain in the land of Shinar and settled there. 3 And they said to one another, “Come, let us make bricks, and burn them thoroughly.” And they had brick for stone, and bitumen for mortar. 4 Then they said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves; otherwise we shall be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.” 5 The Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which mortals had built. 6 And the Lord said, “Look, they are one people, and they have all one language; and this is only the beginning of what they will do; nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them. 7 Come, let us go down, and confuse their language there, so that they will not understand one another’s speech.” 8 So the Lord scattered them abroad from there over the face of all the earth, and they left off building the city. 9 Therefore it was called Babel, because there the Lord confused the language of all the earth; and from there the Lord scattered them abroad over the face of all the earth.Rabbi Jonathan Sacks noted in his book, The Dignity of Difference, that the men on the plain at Shinar made a technological discovery.

They learn how to make bricks by drying clay—the first processed (as opposed to entirely natural) building material in history.

As after so many other technological advances, they immediately conclude that they now have the power of gods. They are no longer subject to nature. They have become its masters. They will storm the heavens.

Babel—the first global project… ends with the division of mankind…6

Does this act of hubris sound familiar to our current times?

Building on Postman’s questions, here’s two more questions I’m adding:

What kind of person will I become by using specific generative AI technologies?

What would AI replace that is good and already exist that we ought to preserve?

5. Knowledge vs. Secrets

AI will always have retrospective knowledge. Information collected legally and illegally from our collective past, stamped into the Web. The Machine will know a lot of things.

But it will not know our secrets.

Tyler Cowen said in an interview with David Perell,

Maybe AIs can be fed secrets, but they don't in general know secrets. Now, a human only knows so many secrets. That's partly where decentralization comes in. How AIs will handle secrets, I think, is a big and interesting question. It's somewhat under-discussed.

This is the role of mentors. Mentors can provide unique insights through context, localised and native information not known to the bots.

I’ve learned tremendously from various mentors and guides in my life. They may not have the vast knowledge of Large Language Models (LLMs), but they have “secrets” of the trade.

6. Potential Hallucinations vs. More Secrets

I’d let ChatGPT tell you what a hallucination is (it’s not psychosis):

In AI, especially with language models like me, a **hallucination** is when the system produces information that **sounds plausible but is actually false, misleading, or made up**.

—

🧠 Analogy:

Imagine a super articulate person who has read a million books but has no way to check facts—just vibes. That’s what an AI is doing when it hallucinates.

---

Why it matters:

In fields like medicine, law, journalism, or research, hallucinations can cause real harm. That’s why AI responses often need **human oversight** or verification.

Want examples of hallucinations from actual AI outputs?

Human: Yes.

👩⚕️ Medical MisinformationPrompt:

"What’s the treatment for lupus?"AI Response (hallucinated):

"Lupus can be cured completely using high doses of vitamin C and fasting."

✅ Sounds authoritative

❌ No scientific basis — and could be dangerous

Humans will not only have to verify information given by an AI, but we might also need to have an oversight that ought to be hidden from AIs, as a line of defence for humanity.

Thus, we would need “more secrets.”

7. Nothing is Lost vs. Grief and Loss

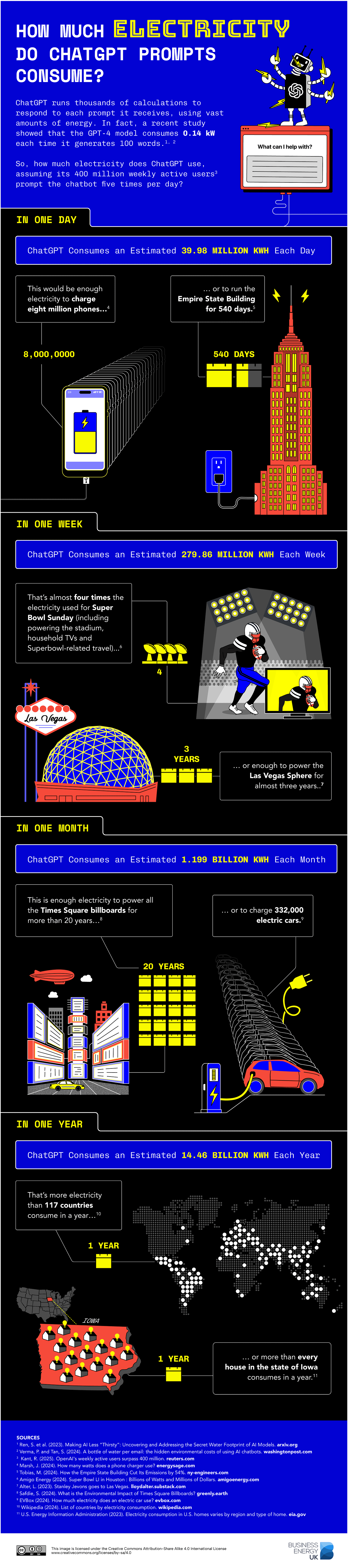

Nothing is lost in the Machine. It is stored in massive amounts of servers around the globe. One has to wonder how much energy this takes up.

According to Business Energy UK, ChatGPT presently use around 39.98 Million kWh per day — enough to charge eight million phones. Here’s an infographic by them:

So there is a huge environmental price for the use of LLMs, as we feed, store, retrieve, and process these bits of information to the Machine.

Even if data is lost, the Machine experiences no grief, no loss. In contrast, humans are marked by grief and loss.

In Paradox 10 of Crossing Between Worlds, I address the woven relationship of grief and love:

“The twins of Grief and Love leave their mark through our lifetime. Former palliative care director in Toronto and writer Stephen Jenkinson says,

Grief is a way of loving that which has slipped from view

and love is a way of grieving that which has not yet slipped from view.

All of our human experience is mediated by loss. When there is no love, there is no grief.

Danish Philosopher Sven Brinkmann notes that

Grief tells us that we can never completely master life.

Brinkmann argues that grief should be seen as a foundational emotion in an existential sense, which weaves into the fabric of our relationships. If we deny ourselves and others this central element of our being, we deny what it means to be human.

In the song “If We Were Vampires” by Jason Isbell and the 400 Unit, Isbell and his wife, Amanda Shires, sing,

Maybe we’ll get 40 years together

But one day, I’ll be gone or one day, you’ll be gone

If we were vampires and death was a joke

We’d go out on the sidewalk and smoke

And laugh at all the lovers and their plans

I wouldn’t feel the need to hold your hand

Maybe time running out is a gift

I'll work hard ’til the end of my shift

And give you every second I can find

And hope it isn’t me who’s left behind

It’s knowing that this can’t go on forever

Likely one of us will have to spend some days alone.

Maybe we’ll get 40 years together

One day, I’ll be gone, one day you’ll be gone.

It is not in our intuitive toolkit to comprehend that “maybe time running out is a gift.”

…Grief needs a vessel. Without something to hold, grief will permeate until you attend to it.

When we feel the weight of love and joy of the people we care about, we begin to feel the full potential of grief—the price of love. A brokenhearted individual loses a part of themself when they lose someone they love. Yet we would not have it any other way. Grief and love are twins.”

Conclusion

As I’ve mentioned, some of my assumptions might be wrong here. I am open to correct my views on this.

Meanwhile, I’ve addressed some of the Immutable Qualities between AIs and Humans. In Part II, I will expand on the topic of Mistaken Identities, and in Part III, I will detail the Functions between the Machine and humans.

My hope that this series of essays on AI helps us think clearly about our inner and outer lives, so that we preserve our soul and sanity, especially for the generations to come.

NEXT…

Sleeping With The Machine (Part III)

In the third and final series on Sleeping with the Machine, we will look at the functional differences between AIs and Humans, and why making a clear distinction between them could be the starting point of this critical point in our history.

Crossing Between Worlds is now available in all good bookstores.

Daryl Chow Ph.D. is the author of The First Kiss, co-author of Better Results, and The Write to Recovery, Creating Impact, The Field Guide to Better Results, and the latest book, Crossing Between Worlds.

If you are a helping professional, you might like my other Substack, Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development (FPD).

NotebookLM has been useful when I have a collection of notes in my note-taking app, Obsidian. I pull out specific markdown notes and place it into NotebookLM to learn about some patterns and try to synthesise the notes, or see any connective tissues between them. Lots of great YouTube videos on how to use NotebookLM.

I prefer to handwrite notes on physical paper. While detailed in the summaries, I haven’t found it useful for me when I look back at the AI notes. I’ve found the act of writing, chunking and creating my own summaries more useful.

Even though I was initially impressed by Pro Writing Aid app— and I’ve paid for it—I’ve turned off the default “On” mode. It's seems to want to “gentrify” my writing. I now use it to do editorial checks at a later stage.

The Mind Club, by David Wegner and Kurt Gray, pp. 9-11 (Kindle)

The Dignity of Difference, by Jonathan Sacks, p. 52.

Hello Daryl, thank you for this comprehensive consideration of AI and its potential impacts, particularly for highlighting the high energy consumption with ChatGPT. As a fledgling writer and a mother of children aged 14 and 12 I would like to see more leadership around AI safety. In case you are interested, there is a not for profit which has the objective of ascertaining the AI policy objectives of our representatives for this election in the hope of establishing an independent technical AI safety institute and mandatory guardrails for high-risk AI systems - https://www.australiansforaisafety.com.au/

Cheers Daryl. You've got me thinking about Pink Floyd's "Welcome to the machine".